Inspired by the [Akamai State of the Internet report](https://web.archive.org/web/20160708134821/https://www.akamai.com/us/en/our-thinking/state-of-the-internet-report/global-state-of-the-internet-connectivity-reports.jsp), this post is about the state of connectivity in Guatemala. Guatemala was chosen because it is one of the countries that uses the Yo! app the most, and is in our target markets. It is also quite different from what I am used to in Canada, and I am interested to know more about it from a connectivity point of view myself. In the 2016 Q1 report, this country is only mentioned in one section — web page load times.

Page Load Times from the Akamai 2016 Q1 report

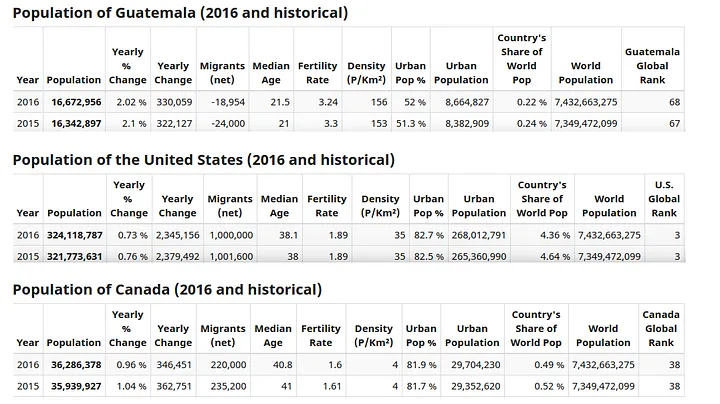

The numbers in the left column are the average broadband load times and the middle column is the average mobile load times, both in ms. In broadband, Guatemala is around middle of the pack, while the mobile load times is one of the fastest. It is interesting that in comparison with large wealthy countries like Canada and the United States, Guatemala and many other LATAM counties actually have more responsive (in terms of delay) mobile networks than broadband networks.

However, this isn’t the whole story — this is only the average time it takes to load a page. It is dependent on size of content — perhaps people have gotten used to limitations of the network and don’t request rich, large images, video and similar content like they do in Canada and the United states. Perhaps there is also a difference because of the population densities and the challenges of delivering network coverage and capacity across vast countryside in the United States and Canada compared to Guatemala.

Comparison of Populations & Densities between Guatemala, Canada & USA — http://www.worldometers.info/

As you can see from the densities — Guatemala is much more dense with 156 people per square km versus 35 in USA and 4 in Canada. This may partially explain the better result for mobile numbers. Since Canada and the USA are less dense, it is expensive to deliver consistent service across the country, likely resulting in some worse average results in their mobile networks. Counter-intuitively, it may be slightly better to be in places where density is higher — up to a certain point where the technology becomes the limiting factor rather than economics.

The other side of the story is bandwidth — this will tell more of a story about how much raw data can be pushed and pulled by users in the network rather than just responsiveness for web traffic. Unfortunately, Guatemala does not have reported results for bandwidth / speed in the Akamai report. The last report I can find mention of Guatemala in is [Q1 2014](https://web.archive.org/web/20180511004945/https://www.akamai.com/us/en/multimedia/documents/state-of-the-internet/akamai-state-of-the-internet-report-q1-2014.pdf) — which states Guatemala’s bandwidth at 1.9 Mbps. At that time it had just doubled year over year, so I assume by now it is significantly higher. There are a few other websites reporting results — but there are typically few results so it is difficult to get a really representative number — which is likely why its been left of the list. The last 1000 results on the [testmy.net](https://testmy.net/country/gt) Internet speed test for Guatemala show an average of 6.5Mbps down and 2.7Mbps up (not sure if this is peak or average from the website). Compare this with the United States with 15.3Mbps (avg) 67.8Mbps (peak) and Canada 14.3Mbps (avg) 59.6Mbps (peak).

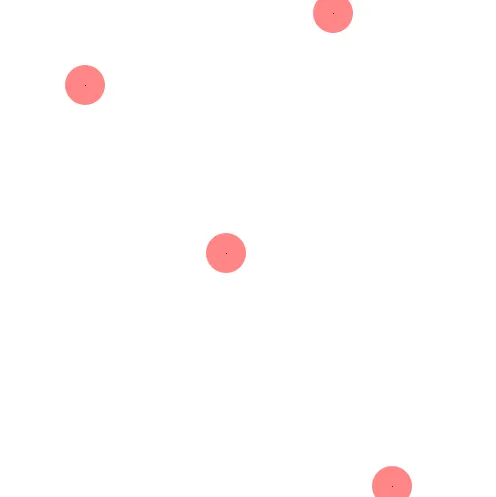

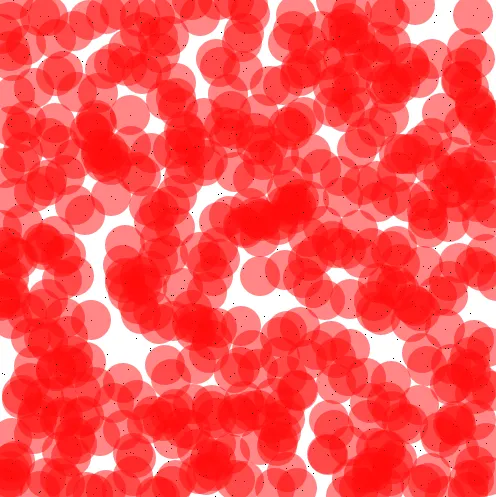

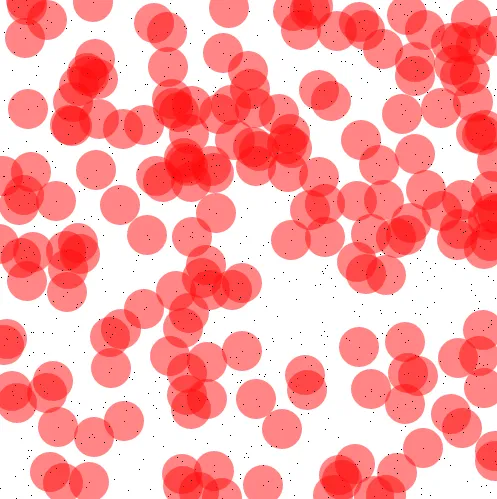

So while these numbers are really an apples and oranges comparison because USA and Canada are very different from Guatemala, it still shows how much the connectivity may be improved. There are other options however, to more effectively use what is available. Wireless mesh networks may provide ways in which more can be squeezed out of what is there. The biggest challenge with meshes is density — let’s see what happens in a country like Canada vs Guatemala. Let’s look at a single square km, and randomly distribute “people” according to the population densities. Each person is represented by a black dot, and the coverage area of a Wi-Fi hotspot will be set to around 20m in a circle (of course in real life this may be farther or shorter, and not a perfect circle due to obstructions, antennas and other factors).

Trying to build a mesh in Canada with 4 people / square km

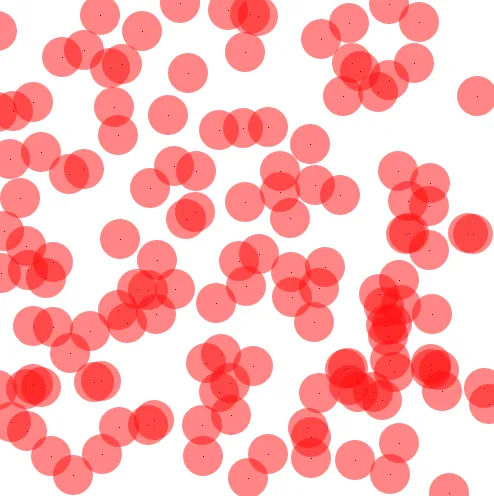

Trying to build a mesh in Guatemala with 140 people / square km

This is an example of the power of increased density when building a mesh. This tool shows what it would be like if everyone in a square km was randomly distributed and all participated in the mesh as a potential hotspot node (the technology we are working on lets you join together multiple hotspots to form a large mesh). The top figure is in Canada where the average density is four people per square km compared with Guatemala which has 140 people per square km. In Canada, the population is far too sparse to build any type of mesh in rural areas. In Guatemala, while it is not possible to connect everyone with a mesh, there are some that can start to form (in order for a mesh to start to form, nodes must be able to see at least another node — so look for black dots covered by darker red).

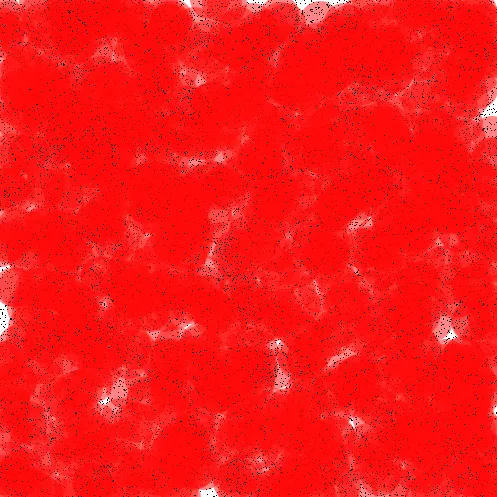

Where it really gets interesting is in cities — this is where the density can really support a mesh well. The next three figures show Guatemala city with various rates of participating as a hotspot node. A hotspot node in this mesh would be able use the mesh and forward traffic for others. The first figure shows 80% participation. Almost every node is covered by at least on other node. The biggest problem here would likely be selecting a good path between nodes or to the Internet.

Guatemala City (roughly 1000 people per sq. km) with 80% participating as hotspot

With only half the nodes participating as hotspots, there are now some dead zones where some of the nodes cannot access the mesh, but there are clear paths all around with very few separate meshes forming.

Guatemala City (roughly 1000 people per sq. km) with 50% participating as hotspot

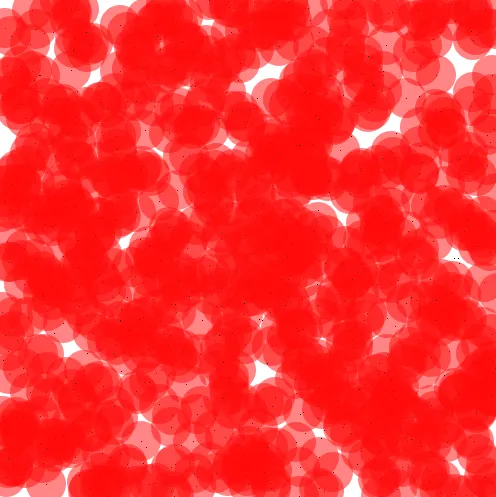

Finally, with only 20% participating, it looks alot more like the rural case, where there are some areas where meshes can form, and some areas where it can’t and lots of users with no coverage whatsoever.

Guatemala City (roughly 1000 people per sq. km) with 20% participating as hotspot

So in cities with similar densities to Guatemala, it is possible to cover the majority of people with somewhere between 20 and 50% participation in a mesh network.

What about an even more dense place — like Dhaka, Bangladesh?

Dhaka, Bangladesh with approximately 24700 people per sq. km and 5% participation.

The entire region can be covered with very few dead zones with only 5% participation. There is still much more that could be learned from this type of tool. For instance, what if we assume some percentage is willing to provide Internet access into the mesh? What percentage of the people will be within 5 hops of the Internet? If each person provides 500mb into the mesh per month, how much bandwidth will each person get per day? If everyone used as much data as they could, how fast would all of the bandwidth in the network be used up? These are all challenges we are trying to solve while also building the technology that is enabling these types of meshes to form.

Countries like Guatemala, Bangladesh, India and others will likely lead the way in mesh deployments. These countries have the density to support the mesh and these countries are also hungry for data, for content and improved connectivity. Infrastructure will always improve in these countries, but meshes will always be a useful way to efficiently connect and distribute information.